This past summer, several of the students in PVL had the opportunity to go through the timeless ritual that all us academics undergo in order to earn our MSc and PhD degrees: the oral defense of our research. I can report that everyone made it through with flying colours! Of course, a defence is also a transition for the student who may be moving from an MSc into a PhD, from a PhD into a Postdoc or from their MSc into the working world, amongst other paths. If you are considering getting a higher degree and want to know what this hurdle looks like, or are starting to think about your own defense, Grace has some helpful insight below.

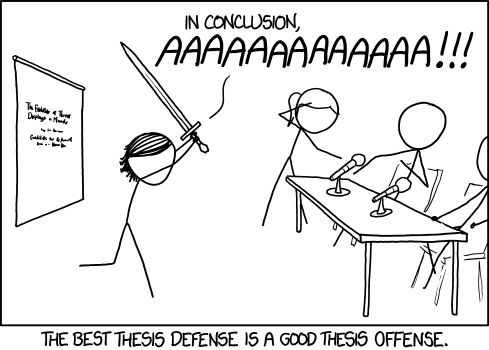

(Image above from XKCD Comics: https://xkcd.com/1403/)

by Grace Bischof

The end of the summer marked a busy time in the Planetary Volatiles Lab. Conor, Giang and I were each nervously preparing for our upcoming thesis defences, where we would learn if we were to pass and obtain our degrees, or fail and be very, very sad. Giang, reaching the end of his PhD in August, defended first, setting the tone for the rest of us by passing! Conor and I followed, defending on September 7th and 8th (apologies to our shared committee members who had to sit in back-to-back defences). Conor and I were also successful in defending our theses, meaning we both obtained our master’s degrees. It was a very exciting end to the summer.

So, what is a thesis defence and why is it so nerve-wracking? In a research-based degree, the findings of the research you complete over several years get written up into a document – at York, this is a thesis for a master’s and a dissertation for a PhD, which is a more robust document than a thesis. This document represents years of hard work, and hopefully, makes an original contribution to the field in which you’re studying. That, in and of itself, is a nerve-wracking process. But before the university can award you your degree for all the painstaking effort you have put into your thesis, they first must test you on the contents in the form of an oral examination.

The oral examination usually begins with a public talk, where your research is presented in a 20 minute to hour long (depending on the degree) presentation. Typically, anyone can join this portion of the defence, and for me, it was fun having my friends and family watch my presentation so they could finally stop asking what it is I actually work on. Once the public talk is over, everyone else leaves the room, so it is just you and your committee. One-by-one, the committee members take turns dissecting your thesis, asking questions, and making suggestions about the contents to facilitate discussion on your work. This process can last several hours, especially for a PhD defence which is more involved. Once the committee has run out of questions to ask, you are kicked out of the room while they deliberate. Sitting outside the room while a small number of people decide the fate on the culmination of your work is horrifying. Then you are finally called back to the room to receive to your verdict…

The good news: the thesis defence is largely a formality. That is, if your research supervisor is doing their job, you will not walk into the thesis defence if you are not going to pass. The purpose of the defence is simply to ensure the student understands their work and the literature in which it is situated. Not knowing the answer to an examiner’s question does not mean you will fail the defence. In fact, the examiners want to see you reason through their questions, applying your knowledge even when you do not have the exact answer. There was one point in my defence when I answered a question completely incorrectly but realized my error once I thought more about it. I told the committee that the answer I gave was incorrect and walked them through my thought process to answer the question correctly. The committee was more interested in seeing my reasoning in getting to the answer than they were worried about the initial mistake I made.

So, now that you know what a thesis defence is, let’s briefly walk through some tips for the defence:

- Start preparing early. The amount of time needed to prepare is going to depend on the degree being obtained – i.e., PhD students will likely need to start earlier than master’s student. Three weeks out before my defence I began to seriously prepare. I started by compiling a list of the most important references in my thesis. I read a handful of these a day, highlighting and jotting down notes on important aspects of each paper. At this time, I was also walking through the basics of the field – sure, it might impress your committee to describe in detail all the aspects of radiative transfer in the atmosphere, but that might diminish if you forget Mars is the 4th planet from the sun.

- Anticipate questions. About 1.5 weeks from the defence date, I began combing through my thesis line by line. I had a PDF version of my thesis which I used to highlight and make notes in the margins. I wrote down anything that came to mind when reading my work and how the committee might interpret it. Some common questions that are asked in defences are: “How does your work fit into the existing literature”; “Describe your work in a few short questions”; “In what ways can this work be expanded?”; “What limitations did you experience in this work?”. Funnily enough, I prepared for all these questions and did not get asked any of them. However, preparing for them helped me to pick apart my work more carefully, meaning I could answer the questions they did give me.

- Try to relax as much as possible. It’s easier said than done. An important tip that I read online before defending my thesis was to make sure that in your state of nervousness, you don’t consistently interrupt the examiners while they are asking questions in an attempt to quickly prove you know the answer. When an examiner is speaking, it’s a perfect time to collect your thoughts and let them talk (it eats up more time this way too!). But, like I said, the defence is largely a formality. If you’ve done the work, then you know your stuff and you will crush it! You are allowed to sit and think about your answer before speaking, drink some water or have a snack, and take a break during the defence if needed. After the first 30 minutes of the defence, the rest breezes by.

Your thesis defence will probably be the only time you will ever have a discussion with people who have ever read the full contents of your thesis. That itself is a pretty cool opportunity, so try to enjoy it as much as you can! Hopefully in four years’ time, when I’m preparing for my PhD defence, I can come back to this blog post and try to take my own advice.